Horloge armillaire à eau de Kaifeng – 1092

Bibliographie

Jacques PIMPANEAU Chine Culture et Traditions, Ed Philippe Picquier

Page 110: « l’horloge à Kaifeng de 1092 », « globe céleste (hunxiang) une sphère armillaire (hunyi) », « en effet bien avant Tycho Brahe, les Chinois localisaient la position d’une étoile d’après sa distance à l’étoile polaire et son degré sur l’équateur céleste qui était divisé en xiu »

Sopie Ann TERISSE Prestigious Watches, BW Publishing, Inc in association with Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Pages 31-32-33

Iron Tower

Erected in 1049 during the Northern Song Dynasty, the 13-story octagonal Iron Tower is situated in the Iron Tower Park in Kaifeng, 55.88 meters in height. It has been renowned for its excellent, exquisitely-designed wooden structure. The bricks with carved trenches fit together perfectly.

Erected in 1049 during the Northern Song Dynasty, the 13-story octagonal Iron Tower is situated in the Iron Tower Park in Kaifeng, 55.88 meters in height. It has been renowned for its excellent, exquisitely-designed wooden structure. The bricks with carved trenches fit together perfectly.

Five Dynasties

Later Liang 907 – 923 Kaifeng

Later Tang 923 – 936 Luoyang

Later Chin 936 – 946 Kaifeng

Later Han 947 – 950 Kaifeng

Later Chou 951 – 959 Kaifeng

Sung

Northern Sung 960 – 1127 Kaifeng

Southern Sung 1127 – 1279 Hangchow

Yuan

1279 – 1368 Peking

Kaifeng

Situated on the southern bank of the Yellow River, Kaifeng is an important city in Henan province, covering an area of 319 square miles with a population of half a million.

With a recorded history close to 3,000 years, Kaifeng is known as one of the six major centers of ancient Chinese civilization. As early as the Yin-Shang period (1334-1066 B.C.), when Chinese society turned away from nomadic life to an agricultural existence, a city was built there. It then became the capital of the Kingdom of Wei in the Warring Sates Period (475-331 B.C.), the Liang, Han and Zhou dynasties of the five Dynasties (907-960). the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1137) and the Jin Dynasty (1115-1334). The Northern Song, in particular, established its capital in Kaifeng for 168 years. The Eastern Capital, as Kaifeng was then called, was the political, economic and cultural center of the whole country, with well-developed handicrafts, bustling commerce and good communication facilities. An old saying went that « Kaifeng was unsurpassed anywhere in splendor and prosperity ».

Repeated Yellow River floods, caused damage to the ancient capital of Kaifeng, and many of its historical relics were destroyed. Among those that have survived are the « Iron » Pagoda, Pota Pagoda, Dragon Pavilion, Xiangguo Monastery, King Yu’s Terrace and Yanqing Taoist Temple. These are all fine works of architecture. Their majestic beauty bears testimony to the wisdom and the high cultural and artistic level their creators attained.

The city today has well-developed commerce, transport, communications and educational facilities, and medical and public health services. The Yellow River that flooded its banks and wrought havoc for a thousand years has been harnessed. The liuyuan Ferry at Kaifeng is now open to tourists as a scenic spot.

JEWISH COMMUNITY

Believe it or not there is a Jewish community in Kaifeng made up of several Chinese Jews. The ancestors of these jews were said to have arrived in China from Persia and India during the Tang Dynasty.

For centuries, the Jews of Kaifeng uttered the prescribed daily and Sabbath prayers, kept their religious holidays and observed strict diets

SONG CITY

Kaifeng was a Song Dynasty capital for many years. Ask your guide to take you to the « Song City », a street flanked by small shops and taverns a thousand years ago.

The street is now under reconstruction on the old Imperial Street between the ancient imperial palace and another street called Sihoujie.

The palace has already been restored, and is open to the public. And another major part of the street, Xuandemen, will soon be completed.

Index-China

14-Henan Kaifeng/Zhengzhou

Clepsydra and Water Wheels

The clepsydra, or water stealer, was a toll created by the Greeks. To measure time, they marked the regulated flow of water through a small opening, such as a bucket with a tiny hole pierced in the bottom. Farmlands from this time were given an allotted supply of water to measure services. When the bucket ran dry, the farmer would pay for that « bucketful » of time.

Because recorded examples of the various clepsydras are rare, early water clocks are often missing from horological timelines. There are some examples. Buddhist monk and mathematician I-Hsing developed an astronomical clockwork instrument in 723 A.D. that he called the « Water-Driven Spherical Bird’s-Eye-View Map of the Heavens. » In addition, animal-powered mills known as « dry-water mills » appeared in China as early as 175 A.D. They had as their precursors hydraulic mills. The Chinese are also credited for creating what is believed to be the first water-based clock, though there is speculation that examples also existed in Islam. One Islamic clock was driven by the weight of a large float, perhaps a block of wood, contained in a tank from which water would drain at a controlled speed. As the float descended with the falling water level, its weight operated the clock mechanism.

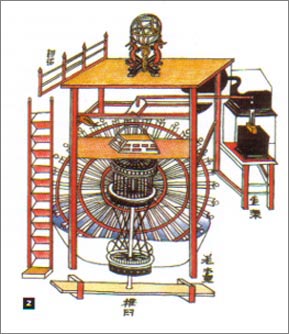

The most famous water clock, however, was made in China. In 1090, in the capital of the Northern Sung dynasty, a government official named Su Sung constructed a 40-foot clock which he called the « Cosmic Engine. » He built the clock using a wooden model and later cast the working parts in bronze. The towering structure had a complex interior mechanism described by contemporaries as « the soul of the time keeping machine. » The mechanism and its « hooks, pins, interlocking rods, coupling devices, and locks checking mutually. » Is believed to be the world’s first escapement. This is a mechanism used in modern clocks, consisting of a rotating, notched wheel and an anchor, which alternately engages and disengages to control the movement of the wheel.

Sung’s clock was powered by water held in a reservoir which was refilled periodically by a manually operated noria. The noria resembled a ferris wheel and consisted of a wheel with buckets attached to its rim. The water from the reservoir was siphoned to a constant level water tank, where it was scooped up by a large waterwheel which turned the clock. The waterwheel turned a series of shafts, gears, and wheels, which in turn worked the bells and drums that announced the time.

Simultaneously, the escapement kept the movement of an even pace by a complex arrangement of balances, counterweights, and locks. Together these mechanisms divided the flow of water into equal parts by repeated weighing, automatically dividing the revolution of the wheel into equal intervals.

Another element of Sung’s water clock was its celestial globe, a spherical model showing the positions of the stars and other celestial bodies. The clock also contain an armillary sphere, another astrological model consisting of several solid rings, all circles of a single sphere, used to display relationship among the principal planets. A chain continually and slowly turned the armillary sphere and globe.

The clock’s 40-foot tower was destroyed by the Chin Tartars, who captured Kaifeng in1126 and brought the clock to Peking. Sung’s creation has only recently been recognized as a precursor to modern clock making. Other mishaps threatened the clock’s place in history. In 1195 the armillary sphere was struck by lightening but later repaired. Then, the precious celestial globe was melted down for scrap and ruined. By the time the Mongols took Peking as their own capital in 1264, the clock itself wasn’t working. Ultimately, even Sung’s magnificent escapement was lost, and Chinese clockmakers returned to using the clepsydra. In the 14th century, the remains of Su Sung’s mechanism were completely destroyed when the Ming dynasty captured Peking. A contemporary sadly reported, « Now it is said that the design is no longer known, even to the descendants of Su Sung himself. » So in the 17th century, when Jesuit missionaries brought a European mechanical clock to China, the device was hailed by the Chinese as a new European invention of dazzling ingenuity. » Sung’s work had been forgotten.

While the early water clocks created by I-Hsing and Su Sung overcame the challenge of darkness faced by the sundial, they also had a basic flaw: they froze in cold weather. The sand hourglass remedied that problem but was subject to harden with moisture absorption until the glassmaker’s art evolved and glass could be made watertight. Even candle-clocks, which seemed a promising solution, were confined to the use by the wealthy due to their need for constant upkeep.

Despite their faults, however, the water clocks evolved into a system of time measurement which became widely used throughout Europe. A 1268 slate was found by the Abbey of Villers outside Brussels, Belgium, which commanded: « You shall pour water from the little pot that is there, into the reservoir until it reaches the prescribed level, and you must do the same when you set the clock after compline, the final evening service, so that you may sleep soundly. » Similarly, a Rule for Cistercian monks stated that the « sacrist roused by the sound of the clock shall ring the church bell. »

Prestigious Watches, Edited by Sophie Ann Terrisse, pages 31/34

Au niveau de la représentation de l’horloge armillaire, j’ai vu une seconde représentation très différente. Elle figure en couverture d’un ouvrage :

Heavenly Clockwork, The great astronomical clocks of medieval China, Joseph Needham, Wang Ling and Derek J. de Solla Price, Second edition with supplement by John H Combridge. (photocopie de faible qualité)

Petite recherche bilingue sur l’horloge armillaire de Kaifeng, via Internet et diverses documentations et ouvrages.